Tenrikyo

| Part of a series on |

| Tenrikyo |

|---|

|

| People |

| Scripture |

| Supplemental texts |

| Beliefs |

| Practices |

| History |

| Institutions |

| Other |

|

Tenrikyo (天理教, Tenrikyō, sometimes rendered as Tenriism)[1] is a Japanese new religion which is neither strictly monotheistic nor pantheistic, originating from the teachings of a 19th-century woman named Nakayama Miki, known to her followers as "Oyasama".[2] Followers of Tenrikyo believe that God of Origin, God in Truth,[3] known by several names including "Tsukihi,"[4] "Tenri-Ō-no-Mikoto"[5] and "Oyagamisama"[6] revealed divine intent through Miki Nakayama as the Shrine of God[7] and to a lesser extent the roles of the Honseki Izo Iburi and other leaders. Tenrikyo's worldly aim is to teach and promote the Joyous Life, which is cultivated through acts of charity and mindfulness called hinokishin.

The primary operations of Tenrikyo today are located at Tenrikyo Church Headquarters, which supports 16,833 locally managed churches in Japan,[8] the construction and maintenance of the oyasato-yakata and various community-focused organisations. It has 1.75 million followers in Japan[8] and is estimated to have over 2 million worldwide.[9]

Beliefs

[edit]The ultimate spiritual aim of Tenrikyo is the construction of the Kanrodai, a divinely ordained pillar in an axis mundi called the Jiba, and the correct performance of the Kagura ritual around the Kanrodai, which will bring about the salvation of all human beings. The idea of the Jiba as the origin of earthly creation is called moto-no-ri, or the principle of origin. A pilgrimage to the Jiba is interpreted as a return to one's origin, so the greeting okaeri nasai ('welcome home') is seen on many inns in Tenri City.

Other key teachings include:

- Tanno (Joyous Acceptance) (堪能) – a constructive attitude towards troubles, illness and difficulties

- Juzen-no-Shugo (十全の守護) – ten principles involved in the creation, which exist in Futatsu Hitotsu (two-in-one relationships) and are considered to be applied continuously throughout the universe

Joyous Life

[edit]The Joyous Life in Tenrikyo is defined as charity and abstention from greed, selfishness, hatred, anger, covetousness, miserliness, grudge bearing, and arrogance. Negative tendencies are not known as sins in Tenrikyo, but rather as "dust" that can be swept away from the mind through hinokishin and prayer. Hinokishin, voluntary effort, is performed not out of a desire to appear selfless, but out of gratitude for kashimono-karimono[10] and shugo (providence).

Ontology

[edit]The most basic teaching of Tenrikyo is kashimono-karimono (貸物借物 or 貸し物借り物), meaning "a thing lent, a thing borrowed". The thing that is lent and borrowed is the human body. Tenrikyo followers think of their minds as things that are under their own control, but their bodies are not completely under their control.[11]

God

[edit]The sacred name of the single God and creator of the entire universe in Tenrikyo is Tenri-Ō-no-Mikoto (天理王命). Tenri-Ō-no-Mikoto created humankind so that humans may live joyously and to partake in that joy. The body is a thing borrowed, but the mind alone is one's own, thus it is commonly accepted that Tenri-Ō-no-Mikoto is not omnipotent.

Other gods are considered instruments, such as the Divine Providences, and were also created by Tenri-Ō-no-Mikoto.

Tenrikyo's doctrine names four properties of Tenri-O-no-Mikoto: as the God who became openly revealed in the world, as the creator who created the world and humankind, as the sustainer and protector who gives existence and life to all creation, and as the savior whose intention in becoming revealed is to save all humankind.[12]

Through her scriptures (the Mikagura-uta, Ofudesaki, and Osashizu), Nakayama conveyed the concept of the divine to her followers in steps:[13][14]

- Firstly as Kami (神, lit. 'spirit/god/deity'). Kami was a familiar term for her followers since they commonly referred to the spirits of the ethnic religion of Shinto, which were worshipped and venerated in Japan. To differentiate this divinity from the Shinto spirits, Oyasama clarified its characteristics with phrases such as moto no kami (元の神, "God of Origin") and jitsu no kami (実の神, "God in Truth").[15][16]

- Secondly as Tsukihi (月日, lit. 'Moon-Sun'). The moon and sun could be understood as visual manifestations of the divine. Just as those bodies impartially give the world light and warmth at all times of the day, the workings of the divine are also impartial and constant.[17]

- Finally as Oya (をや, lit. 'Parent'). The relationship between the divine and human beings is the mutual feeling of love between a parent and his or her children. The divine does not want to command and punish human beings, but rather to guide and nurture them so that they may live joyfully and cheerfully together. Oya (親) is both paternal and maternal, not simply one or the other.[18][19]

These steps have been described as an "unfolding in the revelation of God's nature in keeping with the developing capacity of human understanding, from an all-powerful God, to a nourishing God, and finally to an intimate God."[20]

Followers use the phrase "God the Parent" (Oyagamisama) (親神様) to refer to God, and the divine name "Tenri-O-no-Mikoto" when praising or worshipping God through prayer or ritual.[21]

Causality

[edit]Comparison to karmic belief

[edit]The concept of innen (因縁 (いんねん), "causality") in Tenrikyo is a unique understanding of karmic belief. Although causality resembles karmic beliefs found in religious traditions originating in ancient India, such as Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism, Tenrikyo's doctrine does not claim to inherit the concept from these traditions and differs from their explanations of karma in a few significant ways.

Broadly speaking, karma refers to the spiritual principle of cause and effect where intent and actions of an individual (cause) influence the future of that individual (effect).[22] In other words, a person's good intent and good deed contribute to good karma and future happiness, while bad intent and bad deed contribute to bad karma and future suffering.[23] Causality and karma are interchangeable in this sense;[24] throughout life a person may experience good and bad causality. In Tenrikyo, the concept is encapsulated in the farming metaphor, "every seed sown will sprout."[25] Karma is closely associated with the idea of rebirth,[26] such that one's past deeds in the current life and in all previous lives are reflected in the present moment, and one's present deeds are reflected in the future of the current life and in all future lives.[27] This understanding of rebirth is upheld in causality as well.[28]

Tenrikyo's ontology, however, differs from older karmic religious traditions such as Buddhism. In Tenrikyo, the human person is believed to consist of mind, body, and soul. The mind, which is given the freedom to sense, feel, and act by God the Parent, ceases to function at death. On the other hand, the soul, through the process of denaoshi (出直し, lit. 'to make a fresh start'), takes on a new body lent from God the Parent and is reborn into this world. Though the reborn person has no memory of the previous life, the person's thoughts and deeds leave their mark on the soul and are carried over into the new life as the person's causality.[29] As can be seen, Tenrikyo's ontology, which rests on the existence on a single creator deity (God the Parent), differs from Buddhist ontology, which does not contain a creator deity. Also Tenrikyo's concept of salvation, which is to live the Joyous Life in this existence and therefore does not promise a liberated afterlife outside of this existence, differs from Buddhist concepts of saṃsāra and nirvana.[30]

"Original causality"

[edit]At the focal point of Tenrikyo's ontological understanding is the positing of "original causality," or "causality of origin" (元の因縁 (もとのいんねん), moto no innen), which is that God the Parent created human beings to see them live the Joyous Life (the salvific state) and to share in that joy. Tenrikyo teaches that the Joyous Life will eventually encompass all humanity, and that gradual progress towards the Joyous Life is even now being made with the guidance of divine providence. Thus the concept of original causality has a teleological element, being the gradual unfolding of that which was ordained at the beginning of time.[29]

"Individual causality"

[edit]Belief in individual causality is related to the principle of original causality. Individual causality is divine providence acting to realize the original causality of the human race, which through the use of suffering guides individuals to realize their causality and leads them to a change of heart and active cooperation towards the establishment of the Joyous Life, the world that was ordained at the beginning of time.[31]

Tenrikyo's doctrine explains that an individual's suffering should not be perceived as punishment or retributive justice from divine providence for past misdeeds, but rather as a sign of encouragement from divine providence for the individual to reflect on the past and to undergo a change of heart. The recognition of the divine providence at work should lead to an attitude of tanno (堪能 (たんのう), "joyous acceptance" in Tenrikyo gloss), a Japanese word that indicates a state of satisfaction. Tanno is a way of settling the mind – it is not to merely resign oneself to one's situation, but rather to actively "recognize God's parental love in all events and be braced by their occurrence into an ever firmer determination to live joyously each day."[32] In other words, Tenrikyo emphasizes the importance of maintaining a positive inner disposition, as opposed to a disposition easily swayed by external circumstance.[33]

"Three causalities"

[edit]In addition, The Doctrine of Tenrikyo names three causalities (三因縁 (さんいんねん), san innen) that are believed to predetermine the founding of Tenrikyo's teachings. More precisely, these causalities are the fulfillment of the promise that God made to the models and instruments of creation, which was that "when the years equal to the number of their first born had elapsed, they would be returned to the Residence of Origin, the place of original conception, and would be adored by their posterity."[34] The "Causality of the Soul of Oyasama" denotes that Miki Nakayama had the soul of the original mother at creation (Izanami-no-Mikoto), who conceived, gave birth to, and nurtured humankind. The "Causality of the Residence" means that the Nakayama Residence, where Tenrikyo Church Headquarters stands, is the place that humankind was conceived. The "Causality of the Promised Time" indicates that October 26, 1838 – the day when God became openly revealed through Miki Nakayama – marked the time when the years equal to the number of first-born humans (900,099,999) had elapsed since the moment humankind was conceived.[35]

Texts

[edit]Scriptures

[edit]The three scriptures (三原典, sangenten) of Tenrikyo are the Ofudesaki, Mikagura-uta, and Osashizu.

The Ofudesaki (おふでさき, "Tip of the Writing Brush") is the most important Tenrikyo scripture. A 17-volume collection of 1,711 waka poems, the Ofudesaki was composed by the foundress of Tenrikyo, Miki Nakayama, from 1869 to 1882.

The Mikagura-uta (みかぐらうた, "The Songs for the Service") is the text of the Service (otsutome), a religious ritual that has a central place in Tenrikyo.[a] During the Service, the text to the Mikagura-uta is sung together with dance movements and musical accompaniment, all of which was composed and taught by Nakayama.

The Osashizu (おさしづ, "Divine Directions") is a written record of oral revelations given by Izo Iburi. The full scripture is published in seven volumes (plus an index in three volumes) and contains around 20,000 "divine directions" delivered between January 4, 1887 and June 9, 1907.[37]

According to Shozen Nakayama, the second Shinbashira (the spiritual and administrative leader of Tenrikyo), the Ofudesaki "reveal[s] the most important principles of the faith," the Mikagura-uta "come[s] alive through singing or as the accompaniment" to the Service, and the Osashizu "gives concrete precepts by which the followers should reflect on their own conduct."[38]

Supplemental texts to the scriptures

[edit]The supplemental texts to the scriptures (準原典, jungenten) are officially sanctioned texts which, along with the scriptures, are used to instruct students and adherents of Tenrikyo. They are required texts for students enrolling in Tenrikyo's seminary programs, such as the three-month "Spiritual Development Course" (修養科, Shuyoka).

The Doctrine of Tenrikyo is Tenrikyo's official doctrine, which explains the basic teachings of Tenrikyo. The Life of Oyasama, Foundress of Tenrikyo is Tenrikyo's hagiography of Miki Nakayama. The Anecdotes of Oyasama, Foundress of Tenrikyo is an anthology of anecdotes about Nakayama that were passed down orally by her first followers and later written down and verified.

Organization

[edit]Tenrikyo is subdivided into many different groups with common goals but differing functions. These range from the Daikyokai (lit. 'large church'), to disaster relief corps, medical staff and hospitals, universities, museums, libraries, and various schools.

Tenri Judo is renowned as a successful competition style of Judo that has produced many champions, while there are also other sporting and arts interest groups within Tenrikyo.

History

[edit]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2013) |

In Tenrikyo tradition, Nakayama Miki was chosen as the Shrine of God in 1838, after her son and husband began suffering from serious ailments. The family called a Buddhist monk to exorcise the spirit causing the ailments. When the monk temporarily left and asked Nakayama to take over, she was possessed by the One god (Tenri-O-no-Mikoto), who demanded that Nakayama be given to God as a shrine. Nakayama's husband gave in to this request three days later.

Nakayama's statements and revelations as Shrine of God were supplemented by Izo Iburi, one of her earliest followers, who developed a position of revelatory leadership as her deputy, answering questions from followers and giving "timely talks". His position, which is no longer held in Tenrikyo, was called Honseki. The revelatory transmissions of the Honseki were written down and collected in large, multi-volume works called Osashizu. Following Izo's death, a woman called Onmae partially carried on this role for a while, although it appears that she did not have the actual title of Honseki. Since then, Tenrikyo itself has never had a Honseki, although some Tenrikyo splinter groups believe that the revelatory leadership passed from Iburi to their particular founder or foundress.

Nakayama's eldest son obtained a license to practice branch of Shinto, but did so against his mother's wishes. Tenrikyo was designated as one of the thirteen groups included in Sect Shinto between 1908 and 1945, due to the implementation of Heian policy under State Shinto.[39] During this time, Tenrikyo became the first new religion to do social work in Japan, opening an orphanage, a public nursery and a school for the blind.[40]

Although Tenrikyo is now completely separate from Shinto and Buddhism organizationally, it still shares many of the traditions of Japanese religious practice. For instance, many of the objects used in Tenrikyo religious services, such as hassoku and sanpo, were traditionally used in Japanese ritual, and the method of offering is also traditional.

Timeline

[edit]- 1798, April 18 (lunar calendar) – Miki Nakayama was born.

- 1838, December 12 (October 26, lunar calendar) – God was revealed to Nakayama at the Mishima Shrine.

- 1854 – Nakayama begins to administer the Grant for Safe Childbirth, and thus begins to recruit her first followers.

- 1866 – First chapters of Ofudesaki appear.

- 1887, January 26 (lunar calendar) – the death of Nakayama.

- 1908 – official recognition as one of the thirteen branches of Sect Shinto.

Religious services

[edit]

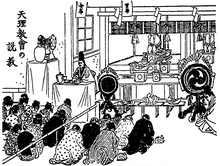

Tenrikyo utilises traditional musical instruments in its otsutome (lit. 'service or duty'), such as hyoshigi (wooden clappers), chanpon (cymbals), surigane (small gong), taiko (large drum), tsuzumi (shoulder drum), fue (bamboo flute), shamisen, kokyū, and koto. These are used to play music from the Mikagura-uta, a body of music, dances and songs created by Nakayama. Most of the world's foremost authorities on gagaku music (the ancient classical Shinto music of the imperial court of Japan) are also Tenrikyo followers, and gagaku music is actively promoted by Tenrikyo, although, strictly speaking, the Mikagura-uta and gagaku are separate musical forms.

The hyoshigi, chanpon, surigane, taiko, and fue were traditionally the men's instruments but are now acceptable for women to play. The shamisen, kokyū, and koto were traditionally women's instruments and, although not very popular, are now acceptable for men to play as well.

Daily services

[edit]The Otsutome (おつとめ, お勤め) or daily service consists of the performance of the seated service and, optionally, the practice of a chapter or two of the 12 chapters of Teodori (lit. 'hand dance') (手踊り) or Yorozuyo. The daily service is performed twice a day; once in the morning and then in the evening. The service times are adjusted according to the time of sun rise and sun set but may vary from church to church. Service times at the Jiba in Tenri City go by this time schedule and adjust in the changing of seasons.

Instruments used in the daily service are the hyoshigi, chanpon, surigane, taiko, and kazutori (a counter, to count the 21 times the first section is repeated). The hyoshigi is always played by the head minister of the church or mission station. If the head minister is not present, anyone may take their place.

The daily service does not need to be performed at a church. It can be done at any time and anywhere, so long as the practitioner faces the direction of the Jiba, or "home of the parent".

The purpose of the daily service, as taught by Nakayama, is to sweep away the Eight Mental Dusts of the mind.

Hinokishin

[edit]Hinokishin (lit. 'daily service') is a spontaneous action that is an expression of gratitude and joy for being allowed to "borrow" his or her body from God the Parent. Such an action ideally is done as an act of religious devotion out of a wish to help or bring joy to others, without any thought of compensation. Hinokishin can range from helping someone to just a simple smile to brighten another person's day. Examples of common Hinokishin activities that are encouraged include cleaning public bathrooms and parks among other such acts of community service. Doing the work that others want to do least are considered sincere in the eyes of God.

Hinokishin is a method of "sweeping" the "mental dusts" that accumulate in a person's mind. The "mental dusts" are referring to the Eight Mental Dusts. The official translations of these dusts are: Miserliness (Oshii), Covetousness (Hoshii), Hatred (Nikui), Self-love (Kawai), Grudge-bearing (Urami), Anger (Haradachi), Greed (Yoku), and Arrogance (Kouman).[41]

The Tenrikyo Young Men's Association and Tenrikyo Women's Association are Tenrikyo-based groups that perform group activities as public service. To participate in such groups may be considered Hinokishin.

Monthly services

[edit]

Tsukinamisai (月次祭) or the monthly service is a performance of the entire Mikagura-uta, the sacred songs of the service, which is the service for world salvation. Generally, mission headquarters and grand churches (churches with 100 or more others under them) have monthly services performed on the third Sunday of every month; other churches perform on any other Sunday of the month. The monthly service at the Jiba is performed on the 26th of every month, the day of the month in which Tenrikyo was first conceived – October 26, 1838.

Instruments used in the monthly service are all of those aforementioned. Performers also include dancers – three men and three women – and a singer. Performers wear traditional montsuki kimono, which may or may not be required depending on the church.

Divine Grant of Sazuke

[edit]

The Divine Grant of Sazuke is a healing prayer in which one may attain through attending the nine Besseki lectures. When one receives the Divine Grant of Sazuke, one is considered a Yoboku (lit. 'useful timber') (用木). The Sazuke is to be administered to those who are suffering from illness to request God's blessings for a recovery. However, recovery requires the sincere effort from both the recipient and the administrator of the Sazuke to clean their minds of "mental dust." Only with pure minds then can the blessings be received by the recipient through the Yoboku administering the Sazuke. It is taught that when God accepts the sincerity of the person administering the Sazuke and the sincerity of the person to whom it is being administered, a wondrous salvation will be bestowed. This is accomplished through having the recipient be aware of the mental dusts and the teachings of Tenrikyo to remedy their dusty minds.

Tenrikyo centers outside Japan

[edit]In recent years Tenrikyo has spread outside Japan, with foreign branches centered primarily in Southeast Asia and America.[42] Tenrikyo maintains centers in:[43][44]

- Argentina: Buenos Aires[45]

- Australia: Calamvale,[43] Melbourne[46]

- Brazil: Bauru,[47] Recife[48]

- Canada: Vancouver[citation needed]

- Republic of Congo: Brazzaville[43]

- Colombia: Cali,[43] Bogotá, Medellín[citation needed]

- France: Paris,[49] Antony[43]

- Hong Kong[43]

- Mexico: Mexico City[50]

- Philippines: Manila (in Makati)[51]

- Singapore[43]

- South Korea: Gimhae[43]

- Taiwan: Taipei[43]

- Thailand: Bangkok[43]

- United Kingdom: Leeds,[citation needed] London[52]

- United States: Los Angeles (US headquarters), Honolulu,[53] Seattle,[54] New York City,[55] San Francisco[56]

Notable followers

[edit]- Avram Davidson – American writer of speculative fiction and crime fiction

- Ayaka Hirahara – Japanese pop singer

- Naoki Matsuyo – Japanese association footballer

- Ronnie Nyogetsu Reishin Seldin – Japanese shakuhachi player

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The importance of the Service to Tenrikyo followers can be appreciated if one understands that the main theme of the Ofudesaki, the most important of the three Tenrikyo scriptures, has been described as "a development toward the perfection of Tsutome, the Service, through which, alone, human salvation can be realized."[36]

References

[edit]- ^ Wolfgang Hadamitzky, Kimiko Fujie-Winter. Kanji Dictionary 漢字熟語字典. Tuttle Publishing, 1996. p. 46.

- ^ Fukaya, Tadamasa, "The Fundamental Doctrines of Tenrikyo," Tenrikyo Overseas Mission Department, Tenri-Jihosha, 1960, p.2

- ^ The Doctrine of Tenrikyo (2006 ed.). Tenrikyo Church Headquarters. 1954. p. 3.

- ^ Ofudesaki: The Tip of the Writing Brush (2012 ed.). Tenri, Nara, Japan: Tenrikyo Church Publishers. 1998. p. 205, VIII-4.

- ^ The Doctrine of Tenrikyo (2006, Fourth ed.). Tenri, Nara, Japan: Tenrikyo Church Headquarters. 1954. p. 29.

We call out the name Tenri-O-no-Mikoto in praise and worship of God the Parent.

- ^ The Doctrine of Tenrikyo (Tenth, 2006 ed.). Tenri, Nara, Japan: Tenrikyo Church Headquarters. 1954. p. 3.

- ^ "I wish to receive Miki as the Shrine of God." The Doctrine of Tenrikyo, Tenrikyo Church Headquarters, 2006, p.3.

- ^ a b Japanese Ministry of Education. Shuukyou Nenkan, Heisei 14-nen (宗教年鑑平成14年). 2002.

- ^ Stuart D. B. Picken. Historical dictionary of Shinto. Rowman & Littlefield, 2002. p. 223. ISBN 0-8108-4016-2

- ^ Sawai, Makoto (3 September 2020). "Salvation Through Saving Others: toward a Tenrikyo-Muslim Comparative Theology for Japan Today". International Journal of Asian Christianity. 3 (2): 216–217. doi:10.1163/25424246-00302008. ISSN 2542-4246. S2CID 234632794. Retrieved 27 July 2022.

- ^ The Doctrine of Tenrikyo Chapter 7: A Thing Lent, A Thing Borrowed pp. 50–57

- ^ A Glossary of Tenrikyo Terms, p.110.

- ^ Tenrikyo, Its History and Teachings, 47-8.

- ^ Fukaya, Yoshikazu. Words of the Path: A Guide to Tenrikyo Terms and Expressions 4–5.

- ^ A Glossary of Tenrikyo Terms, 105, 108–9.

- ^ The Doctrine of Tenrikyo opens with the line, "I am God of Origin, God in Truth."

- ^ A Glossary of Tenrikyo Terms, 454-5.

- ^ A Glossary of Tenrikyo Terms, 274-5.

- ^ Tenrikyo Christian Dialogue, 55.

- ^ Kisala, Robert (2001). "Images of God in Japanese New Religions." Bulletin of the Nanzan Institute for Religion & Culture, 25, p. 23.

- ^ A Glossary of Tenrikyo Terms, p.109.

- ^ Karma Encyclopædia Britannica (2012)

- ^ Lawrence C. Becker & Charlotte B. Becker, Encyclopedia of Ethics, 2nd Edition, ISBN 0-415-93672-1, Hindu Ethics, pp 678

- ^ Kisala, Robert. "Contemporary Karma: Interpretations of Karma in Tenrikyō and Risshō Kōseikai." Japanese Journal of Religious Studies, Vol. 21, No. 1 (Mar., 1994), pp. 73–91: "In accord with traditional karmic understanding, it is the accumulation of bad innen that is offered as the explanation for present suffering."

- ^ Fukaya, Yoshikazu. "Every Seed Sown Will Sprout." Words of the Path. online link

- ^ James Lochtefeld (2002), The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Rosen Publishing, New York, ISBN 0-8239-2287-1, pp 351–352

- ^ "Karma" in: John Bowker (1997), The Concise Oxford Dictionary of World Religions, Oxford University Press.

- ^ Kisala, p.77. "...traditional karmic beliefs in personal responsibility, extending over innumerable lifetimes, are upheld in doctrines concerning individual innen."

- ^ a b Kisala, p.77.

- ^ Tenrikyo-Christian Dialogue, p. 429-430.

- ^ Kisala, p.77-8.

- ^ Doctrine of Tenrikyo, Tenrikyo Church HQ, 61.

- ^ Kisala, p.78.

- ^ The Doctrine of Tenrikyo, p.20.

- ^ A Glossary of Tenrikyo Terms, p.436.

- ^ See Inoue and Eynon, A Study of the Ofudesaki, xix.

- ^ Tenrikyo Overseas Department, trans. 2010. A Glossary of Tenrikyo Terms, p. 72. Note: This work presents an abridged translation of the Kaitei Tenrikyo jiten, compiled by the Oyasato Institute for the Study of Religion and published in 1997 by Tenrikyo Doyusha Publishing Company.

- ^ "The Various Forms of Verbal Evolution in Tenrikyo Doctrine" that was presented at the 10th Congress of the International Association for the History of Religions held in Marburg in 1960.

- ^ The Formation of Sect Shinto in Modernizing Japan Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 29/3-4, Inoue Nobutaka, pp. 406, 416–17

- ^ Isaku Kanzaki. "Present Day Shintoism". In Paul S. Meyer (ed.), The Japan Mission Year Book 1928. Tokyo: Japan Advertiser Press, 1928.

- ^ Mental Dusts Tenrikyo International Website

- ^ Britannica Kokusai Dai-Hyakkajiten entry for Tenrikyo.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Tenrikyo". Tenrikyo (in Japanese). 2021-09-26. Retrieved 2024-12-24.

- ^ "海外の地域拠点". 天理教・はじめてのかたへ (in Japanese). Retrieved 2024-12-24.

- ^ "Tenrikyo Buenos Aires". Archived from the original on 26 December 2015. Retrieved 8 August 2015.

- ^ "Tenrikyo Melbourne Shinyu Church". Retrieved 8 August 2015.

- ^ Igreja Tenrikyo

- ^ Igreja Tenrikyo Hoyo do Nordeste

- ^ "Tenrikyo Europe Centre". Retrieved 8 August 2015.

- ^ Asociación Religiosa Tenrikyo Archived 2009-01-31 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Tenrikyo Mission Center in the Philippines".

- ^ "Tenrikyo UK Centre Official Homepage". Retrieved 8 August 2015.

- ^ "Tenrikyo Mission Headquarters of Hawaii – One world, one family". Retrieved 8 August 2015.

- ^ "Tenrikyo in America and Canada". Retrieved 8 August 2015.

- ^ "TENRI CULTURAL INSTITUTE". Retrieved 8 August 2015.

- ^ "Tenrikyo Churches and Fellowships in the America and Canada Diocese". tenrikyo.com. Retrieved 8 August 2015.