Death Race 2000

| Death Race 2000 | |

|---|---|

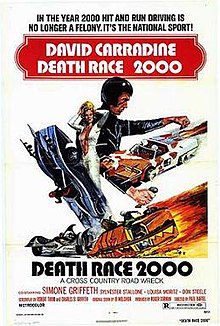

Theatrical release poster by John Solie | |

| Directed by | Paul Bartel |

| Screenplay by | Robert Thom Charles B. Griffith |

| Based on | "The Racer" (1956 short story) by Ib Melchior |

| Produced by | Roger Corman |

| Starring | David Carradine Simone Griffeth Sylvester Stallone Louisa Moritz Don Steele |

| Cinematography | Tak Fujimoto |

| Edited by | Tina Hirsch |

| Music by | Paul Chihara |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | New World Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 80 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $300,000–530,000[1][2][3] |

| Box office | $5–8 million[1][3] |

Death Race 2000 is a 1975 American dystopian science-fiction action film directed by Paul Bartel and produced by Roger Corman for New World Pictures.[4] Set in a dystopian American society in the year 2000, the film centers on the murderous Transcontinental Road Race, in which participants score points by striking and killing pedestrians. David Carradine stars as "Frankenstein", the leading champion of the race, who is targeted by an underground rebel movement seeking to abolish the race. The cast also features Simone Griffeth, Sylvester Stallone, Mary Woronov, Martin Kove, and Don Steele.

Noting the publicity surrounding the film Rollerball (1975), Roger Corman sought to develop his own futuristic sports action film, and optioned the rights to Ib Melchior's 1956 short story "The Racer".[5] Paul Bartel was hired to direct. The film was released on April 27, 1975. It initially received mixed critical reviews but was a considerable commercial success, grossing over $5 million from a sub-$1 million budget.[6]

In the years since its release, critics have praised the film's political and social satire,[7] and it has developed a strong cult following.[5] It spawned 2008 remake, entitled Death Race, and a 2017 sequel film, Death Race 2050.

Plot

[edit]After the "World Crash of '79", massive civil unrest and economic ruin occurs. The United States government is restructured into a totalitarian regime under martial law. To pacify the population, the government has created the Transcontinental Road Race, where a group of drivers race across the country in their high-powered cars and which is infamous for violence, gore, and innocent pedestrians being struck and killed for bonus points. In 2000, the five drivers in the 20th annual race, who all adhere to professional wrestling-style personas and drive appropriately themed cars, include Frankenstein, the mysterious black-garbed champion and national hero; Machine Gun Joe Viterbo, a Chicago gangster; Calamity Jane, a cowgirl; Matilda the Hun, a Neo-Nazi; and Nero the Hero, a Roman gladiator. Joe, the second-place champion, is the most determined of all to defeat Frankenstein and win the race.

A resistance group led by Thomasina Paine, a descendant of the 1770s American Revolutionary War hero Thomas Paine, plans to rebel against the regime, currently led by a man known only as Mr. President, by sabotaging the race, killing most of the drivers, and taking Frankenstein hostage as leverage against Mr. President. The group is assisted by Paine's great-granddaughter Annie Smith, Frankenstein's navigator. She plans to lure him into an ambush in order to have him replaced by a double. Despite a pirated national broadcast made by Ms. Paine herself, the Resistance's disruption of the race is covered up by the government and instead blamed on the French, who are also blamed for ruining the country's economy and telephone system.

At first, the Resistance's plan seems to bear fruit: Nero the Hero is killed when a "baby" he runs over for points turns out to be a bomb, Matilda the Hun drives off a cliff while following a fake detour route set up by the Resistance, and Calamity Jane, who witnessed Matilda the Hun's death, inadvertently drives over a land mine. This leaves only Frankenstein and Machine Gun Joe in the race. As Frankenstein nonchalantly survives every attempt made on his life during the race, Annie comes to discover that Frankenstein's mask and disfigured face are merely a disguise; he is, in fact, one of a number of random wards of the state who are trained exclusively to race under that identity, and each time they die or are brutally mutilated, they are secretly replaced so that Frankenstein appears to be indestructible.

The current Frankenstein reveals to Annie his own plan to kill Mr. President: when he wins the race and shakes hands with Mr. President, he will detonate a grenade which has been implanted in his prosthetic right hand. However, the plan goes awry when Machine Gun Joe attacks Frankenstein and Annie is forced to kill him using Frankenstein's "hand grenade". Having successfully outmaneuvered both the rival drivers and the Resistance, Frankenstein is declared the winner of the race, although he is wounded and unable to carry out his original "hand grenade" attack plan. Annie instead dons Frankenstein's costume and plans to stab Mr. President while standing in for him on the podium. Before she is able to do so, Thomasina shoots "Frankenstein", convinced that he killed Annie. The real Frankenstein takes advantage of the confusion and rams Mr. President's stage with his car, finally fulfilling his lifelong desire to kill him. Frankenstein becomes the new president, marries Annie and appoints Thomasina the Minister of Domestic Security to rebuild the state and dissolve the dictatorship. Junior Bruce, the announcer of the Transcontinental Road Race, opposes the race's abolition and impertinently claims that the public needs performances of violence. Annoyed by his complaints, Frankenstein hits Bruce with his car and drives off with Annie to the cheers and applause of the crowd.

Cast

[edit]- David Carradine as "Frankenstein"

- Simone Griffeth as Annie Smith (Frankenstein's navigator)

- Sylvester Stallone as Joe "Machine Gun" Viterbo

- Mary Woronov as "Calamity" Jane Kelly

- Roberta Collins as Matilda "The Hun"

- Martin Kove as Ray "Nero the Hero" Lonagan

- Louisa Moritz as Myra (Joe's navigator)

- Don Steele as Junior Bruce (race announcer)

- Joyce Jameson as Grace Pander (race announcer)

- Carle Bensen as Harold (race announcer)

- Sandy McCallum as Mr. President

- Paul Laurence as Special Agent

- Harriet Medin as Thomasina Paine

- Vince Trankina as Lieutenant Fury

- Bill Morey as Deacon

- Fred Grandy as Herman "The German" Boch (Matilda's navigator)

- William Shephard as Pete (Jane's navigator)

- Leslie McRay as Cleopatra (Nero's navigator)

- Wendy Bartel as Laurie

- Jack Favorite as Henry

- Sandy Ignon as FBI Agent

- John Landis as Mechanic

- Darla McDonell as Rhonda Bainbridge

- Roger Rook as Radio Operator

- Wendy Dio as Blonde Masseuse

Production

[edit]Development and writing

[edit]Roger Corman wanted to make a futuristic action sports film to take advantage of the advance publicity of Rollerball (1975). He optioned a short story by Ib Melchior, an associate from his American International Pictures days, and hired Robert Thom to adapt it. Director Paul Bartel felt this was unshootable, so Charles B. Griffith rewrote it. Corman referred to the original story treatment as overly-serious and "kind of vile", and reworked it to emphasize satire and camp.[8]

Bartel was hired on the basis of his second unit work on Big Bad Mama (1974), which Corman produced. In a 1982 interview, Bartel said: "Most of my guilty pleasures in this film were ripped out by the roots by Roger Corman before the film ever saw the light of day and substituted with crushed heads and blood squibs. Nevertheless, there is a joke about the French wrecking our economy and telephone system that I still find amusing. And I am pleased by the scene introducing the Girl Fan (played very effectively by my sister Wendy) who is to sacrifice herself beneath the wheels of David Carradine's race car and wants to meet him so that the gesture will have 'meaning'."[9]

Bartel later recalled: "We had terrible script problems; David had to finish his Kung Fu series before starting and we had bad weather. We all worked under terrible pressure. Roger and I had an essential disagreement over comedy. He took out a lot of the comedy scenes. He may have been right and was probably more objective."[1] At one point in production, Bartel and Carradine clashed enough where the director had thought of replacing Carradine with Lee Majors, although they eventually reconciled and had a bond enough to help influence the ending of the film. Corman disagreed with the idea envisioned by Bartel for the ending involving a running over of a reporter character because the producer thought "it would compromise the hero". Instead, Corman thought of an idea where the reporter is instead shot on the spot by FBI agents while Frankenstein makes light of such as "sort of irresponsible question" When it came time to film the ending, Bartel shot the ending seen in the final print without shooting the one envisioned by Corman because Carradine stated he "wasn't interested in fooling with the other one" so the two simply moved on.[10]

Casting

[edit]Corman wanted Peter Fonda to play the lead, but he read the script and said it was too ridiculous to make, so David Carradine was cast instead; Carradine wanted to take on a role that would make people think of him as more than just Caine on Kung Fu and give him a leg up on a movie career. Carradine was paid 10% of the film's gross.[3]

Sylvester Stallone was cast after Corman saw his performance in The Lords of Flatbush (1974).[8] Up until his star-making role in Rocky the following year, Death Race 2000 was the actor's highest-profile performance.[6] At Bartel's direction, Stallone rewrote much of his character's dialogue.

Shelley Winters turned down the role of Thomasina Paine. Character actress and dialect coach Harriet White Medin won the role after doing a pitch-perfect impression of Eleanor Roosevelt at an audition.[11]

Paul Bartel's sister Wendy appears as Laurie, the Frankenstein superfan who sacrifices herself to him.

Leslie McRay, who played Cleopatra, was originally offered the lead role of Annie, but she turned it down because she didn't want to perform nude.

Filming

[edit]Death Race 2000 was shot in locations around Southern California. Cinematographer Tak Fujimoto had previously shot Caged Heat for Corman.

Filming locations included the Chet Holifield Federal Building, the Pasadena Convention Center, Indiana Dunes National Park, and Angeles National Forest. The office complex of Los Angeles Center Studios doubled for "Mercy Hospital". The racetrack scenes were shot at the Ontario Motor Speedway in Ontario, California. The production could not afford large numbers of extras to play the bystanders, so the scenes were shot after an actual racing event.

Due to the film's low-budget, many scenes were shot on public roadways.[8] David Carradine and Sylvester Stallone performed most of their own driving stunts.[8] According to Corman, the custom-built cars were not street legal, and the stunt drivers refused to drive them where they could potentially be apprehended by police.[8] Meanwhile, Mary Woronov did not know how to drive a car, so her close-ups were shot with her car towed behind a flatbed truck.[8]

Music

[edit]The score was written by composer Paul Chihara, his first time writing music for film. Critic Donald Guarisco described Chihara's score as "eclectic ... [mixing] jazz, symphonic, funk, prog and electronica elements to create a constantly-shifting musical background with a delightful retro-futurist feel".[12]

Release

[edit]Home media

[edit]Shout! Factory released a Deluxe Edition DVD and Blu-ray on June 22, 2010, in Region 1/A.[13]

Previous video editions were released on VHS and DVD by Buena Vista Home Entertainment and New Concorde, among other studios.[14]

Reception

[edit]Box office

[edit]According to Variety, the film earned $4.8 million in rentals in the United States.[15] Another account says $5.25 million.[16]

Initial critical response

[edit]Contemporary reviews were mixed. Lawrence Van Gelder of The New York Times wrote that the film had "nothing to say beyond the superficial about government or rebellion. And in the absence of such a statement, it becomes what it seems to have mocked—a spectacle glorifying the car as an instrument of violence."[17] Variety called the film "cartoonish but effective entertainment, with some good action sequences and plenty of black humor."[18] Richard Combs of The Monthly Film Bulletin wrote that the comic conceits were "too shaky to hold the movie together and tend to self-destruct some distance short of any pop allegory for America".[19] Gene Siskel of the Chicago Tribune gave the film one star out of four and wrote that it "may be the goofiest and sleaziest film I've seen in the last five years".[20] Tom Shales of The Washington Post praised the film as "one of the zippier little B pictures of the year", adding that "it is designed primarily as a spectacle of kinetic titillation, and on that level, it's a foregone smash hit".[21] Kevin Thomas of the Los Angeles Times was also positive, calling it "a fine little action picture with big ideas" and finding Carradine "terrific" in his role.[22] In a February 2021 retrospective review, James Berardinelli gave the film 1 star out of 4; he said that it was similar to present-day releases by Blumhouse in that Roger Corman also made a lot of those types of low-budget horror/exploitation films and some were/are good but most are not, and simply summed up the 1975 film by calling it "bad".[23]

Roger Ebert gave the film zero stars in his review, deriding its violence and lamenting its appeal to small children.[24] However, during a review of The Fast and the Furious on Ebert & Roeper and the Movies, Ebert named Death Race 2000 as part of a "great tradition of summer drive-in movies" that embrace a "summer exploitation mentality in a clever way".[25] While Ebert hinted that he did not find the film as awful decades later as he did in 1975, he made it plain he would not alter or disavow his original zero-stars rating for it either.[26][27] He also gave a scathing review of the 2008 reboot Death Race.

Retrospective reviews

[edit]The film has garnered critical acclaim over the years, having a score of 82% on Rotten Tomatoes based on 39 reviews, with an average rating of 6.8/10, deeming it "fresh". The site's critical consensus states, "Death Race 2000 is a fun, campy classic, drawing genuine thrills from its mindless ultra-violence."[7]

The film has long been regarded as a cult hit[5] and was often viewed as superior to Rollerball, a much more expensive major studio drama released later in the same year; another dystopian science-fiction sports film similarly focusing on the use of dangerous sports as an "opiate" for the masses.[5]

Year-end lists

[edit]The film is recognized by American Film Institute in these lists:

- 2001: AFI's 100 Years...100 Thrills – Nominated[28]

Other media

[edit]Video games

[edit]The 1982 video game Maze Death Race for ZX81 computers (and 1983 for ZX Spectrum) resembles the film by its cover artwork, title, and car-driving content.[29]

The Carmageddon video game series borrows heavily from the plot, characters and car designs from the film Death Race 2000. The original game was supposed to be a game based on the comic series in the 1990s, but the plans were later changed.

Comic books

[edit]A comic book sequel series titled Death Race 2020 was published in April–November 1995 by Roger Corman's short-lived Roger Corman's Cosmic Comics imprint. It was written by Pat Mills of 2000 AD fame, with art by Kevin O'Neill (and additional art by Trevor Goring). Mills and O'Neill had already worked together on several comics, including Marshal Law. The comic book series, as the title indicates, takes place 20 years after the film ended and deals with Frankenstein's return to the race. New racers introduced here included Von Dutch, the Alcoholic, Happy the Clown, Steppenwolf, Rick Rhesus, and Harry Carrie.

The comic book series lasted eight issues before being canceled and the story was left unfinished at the end.

Remake series

[edit]Paul W. S. Anderson directed a remake entitled Death Race, which was released August 22, 2008, starring Jason Statham. The remake began production in late August 2007.[30] Besides Statham, this new version also stars Ian McShane, Joan Allen, and Tyrese Gibson.[31] It also includes a cameo (by voice-over) of David Carradine, reprising his role of Frankenstein. Two direct-to-DVD prequels, titled Death Race 2 (2010) and Death Race 3: Inferno (2013), starring Luke Goss, Tanit Phoenix, Danny Trejo and Ving Rhames, and a direct-to-DVD sequel, titled Death Race: Beyond Anarchy (2018), were also produced.

Sequel

[edit]An official sequel film to the original film, Death Race 2050, was produced by Roger Corman[32] and released in early 2017.[33]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Thomas, Kevin (December 21, 1975). "9 Directors Rising From the Trashes". Los Angeles Times. p. m1.

- ^ "Death Race 2000". The Numbers. Retrieved July 24, 2011.

- ^ a b c Koetting, Christopher T. (2009). Mind Warp!: The Fantastic True Story of Roger Corman's New World Pictures. Hemlock Books. pp. 80–83. ISBN 9780955777417.

- ^ "Death Race 2000 (1975)". AllMovie. Retrieved November 16, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Bosnan, John (1998). "Death Race 2000". In Clute, John; Nichols, Peter (eds.). The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction (2nd ed.). London: Orbit. ISBN 9781857231243.

- ^ a b "Death Race 2000 (1975)". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. Retrieved September 16, 2024.

- ^ a b "Death Race 2000 (1975)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved June 17, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f filmSCHOOLarchive (August 20, 2017). Death Race 2000 - Making Of. Retrieved September 16, 2024 – via YouTube.

- ^ Bartel, Paul (September–October 1982). "Paul Bartel's Guilty Pleasures". Film Comment (18.5 ed.). pp. 60–62.

- ^ "Take One Magazine - July 1978". July 1978.

- ^ Lucas, Tim Harriet White Medin Interview Video Watchdog # 22

- ^ "DEATH RACE 2000: The Darkly Witty Flipside Of Dystopian Sci-Fi". Schlockmania. Retrieved September 17, 2024.

- ^ "The Original Death Race Gets the Deluxe Blu-ray and DVD Treatment and More Corman Classics to Come!". Dread Central. April 1, 2010. Retrieved March 21, 2011.

- ^ "Death Race 2000 - Releases". AllMovie. Retrieved October 13, 2023.

- ^ "All-time Film Rental Champs". Variety. January 7, 1976. p. 48.

- ^ Donahue, Suzanne Mary (1987). American Film Distribution: the Changing Marketplace. UMI Research Press. p. 293. ISBN 9780835717762. Please note figures are for rentals in US and Canada

- ^ Van Gelder, Lawrence (June 6, 1975). "The Screen: 'Death Race 2000' Is Short on Satire". The New York Times. p. 17. Retrieved October 13, 2023.

- ^ "Film Reviews: Death Race 2000". Variety. May 7, 1975. p. 48.

- ^ Combs, Richard (February 1976). "Death Race 2000". The Monthly Film Bulletin. Vol. 43, no. #505. p. 27.

- ^ Siskel, Gene (June 22, 1975). "Dismal duo for a drive-in double bill". Chicago Tribune. p. Section 3, p. 5.

- ^ Shales, Tom (June 11, 1975). "'Death Race 2000': Smashing And Ruthless Exploitation". The Washington Post. p. B6.

- ^ Thomas, Kevin (May 2, 1975). "Barbarism in Big Brother Era". Los Angeles Times. p. Part IV, p. 21.

- ^ Berardinelli, James (February 28, 2021). "Death Race 2000 (United States, 1975)". Reel Views. Retrieved October 13, 2023.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (April 27, 1975). "Death Race 2000". RogerEbert.com. Retrieved May 27, 2014.

- ^ "The Fast and the Furious (Year 2001)". Ebert & Roeper and the Movies. Season 16. Episode 3. June 21, 2001. Buena Vista Television. Retrieved October 13, 2023.

- ^ "'Death' Be Not So Good. Still". RogerEbert.com. August 28, 2008. Retrieved July 31, 2017.

- ^ "Those Coen boys, what kidders". RogerEbert.com. September 11, 2008. Retrieved July 31, 2017.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Thrills Nominees" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 13, 2011. Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- ^ "ZX81 Cassette Tape Information for Maze Death Race". Zx81stuff.org.uk. Retrieved August 13, 2012.

- ^ Graser, Marc; Garrett, Diane (June 1, 2007). "Film: Universal Restarts 'Spy Hunter'". Variety. Retrieved June 1, 2007.

- ^ "Ian McShane Joins Death Race". ComingSoon.net. August 8, 2007. Retrieved August 8, 2007.

- ^ Alexander, Chris (April 6, 2016). "Roger Corman Turns 90! Releases BTS Stills from DEATH RACE 2050!". ComingSoon.net. Retrieved January 16, 2017.

- ^ Alexander, Chris (January 10, 2017). "Roger Corman's Death Race 2050 Blu-ray Review". ComingSoon.net. Retrieved January 16, 2017.

External links

[edit]- 1975 films

- Death Race (franchise)

- 1975 independent films

- 1970s action adventure films

- 1970s dystopian films

- 1970s road movies

- 1970s science fiction action films

- American independent films

- American road movies

- American satirical films

- American comedy films

- American science fiction action films

- 1970s English-language films

- Films directed by Paul Bartel

- Films produced by Roger Corman

- Films scored by Paul Chihara

- Films with screenplays by Charles B. Griffith

- Films based on American short stories

- Films based on science fiction short stories

- American dystopian films

- Films set in 2000

- Films set in the future

- New World Pictures films

- Fictional motorsports

- Motorsports in fiction

- Fiction about politics

- Sports fiction

- American action adventure films

- American exploitation films

- 1970s American films

- English-language independent films

- Films set in St. Louis

- 1975 science fiction films

- English-language science fiction action films

- English-language action adventure films